Pre-order Music For Prototype Vol. 1 here

The house was relatively small, little more than a two-up two-down, but it was big enough for my needs and was in good condition despite being uninhabited for some time. After spending a couple of days unpacking and arranging the essentials, I decided to tackle the outbuilding, which was situated a short distance from the property in an established, but unnoteworthy garden that was itself larger than the footprint of the house.

When I was given my first and only viewing a few months earlier, the agent didn’t have a key for the padlocked door to the windowless brick-built structure in the garden. She assured me that she had been inside and that the space was empty and dry. I could see for myself that the tiled roof was intact, but who knows with a building several decades old? It was a risk to commit with looking inside, but I imagined that the space would be perfect for conversion into a little music studio and workspace, hopefully without the need for any substantial structural works.

The old padlock broke easily with a pair of large bolt cutters I’d bought from a car boot sale several years earlier but had, until then, found no use for. Opening the solid oak door (situated on one of the shorter sides of the building) and expecting concrete and dank, I was astounded to find the walls, floor and rafters were clad with wood. Not a cheap laminate, but some variety of hardwood. It was dry, as I had been told it would be, and a thin layer of dust covered the floor and the large, covered object that stood slightly offset from the far-left corner. I approached, creating fresh footprints through the dust which I would later appreciate as a visual metaphor for the “one small step for man” journey I was about to embark upon.

The object was protected by a well-fitted faux leather cover. As I removed it, the not inconsiderable veneer of dust filled my face, causing me to shield my eyes with one arm and hack a cough whilst ungracefully pivoting to face the only source of fresh air in the opposite corner. Upon turning back, through settling dust and illuminated only by sunlight from that open door, I was awestruck to find myself looking at what was clearly a musical instrument, one both familiar and highly unusual. I had certainly never seen nor read a description of anything quite like what stood before me.

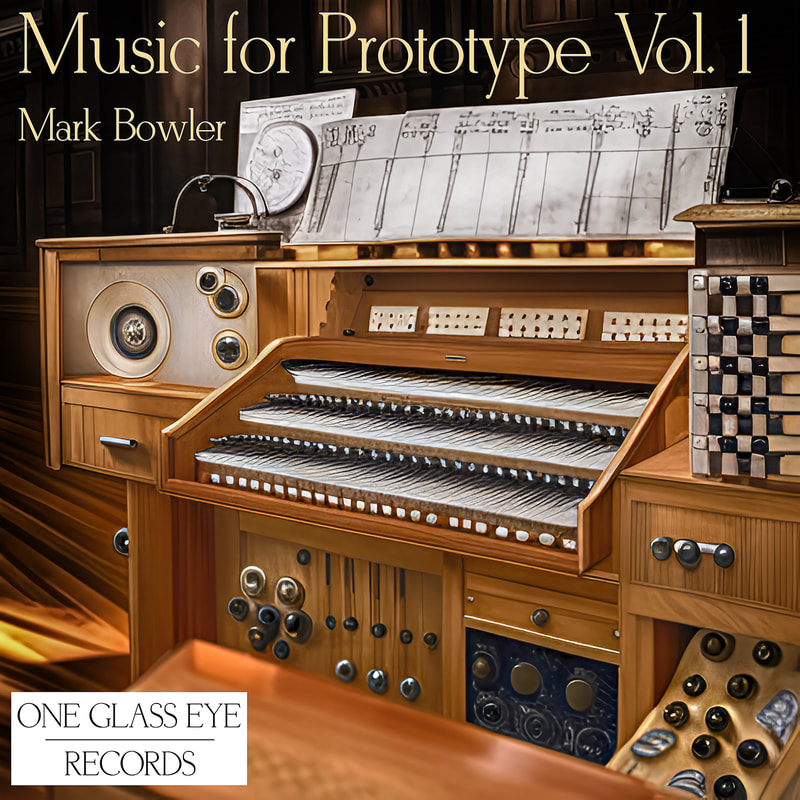

At first glance it was an organ with three manuals and foot pedals (and there the familiarity ended) set inside what I later found to be an exquisitely crafted wooden casing, which could only have been made by an expert cabinet maker. The seat was joined to the man body of the instrument at its base in such a way that as I entered the console area I had to step up approximately 10cm onto a platform base, on top of which was fixed the box-like seating bench.

Built into the cabinet were a pair of speakers, one either side of an unusual set of a solid-wood buttons and controls which parenthesised the keyboards in a vertical orientation. Each speaker consisted of a large driver with three small tweeters. Like the rest of the instrument, they looked to be of bespoke design. Beneath each speaker was a drawer, but I found both to be empty.

Speakers, I knew, meant electricity. This led me to the power cable that trailed from a small hole in the rear panel to a standard 240v three-pin socked, which appeared to be the only source of electricity in the building. Flicking the switch on this socket resulted in a little pop, exactly as you would expect when turning on the power to an amplifier if the volume hadn’t been turned down. After that, silence. I found myself surprised that there was no trace of electrical hum and wondered if I would be faced with disappointment when I attempted to create sound with the instrument.

I sat at the console, which was accessed from the left side of the instrument, the same side that faced the open door. The vertically set controls on either side of the keyboard had a piano-like aesthetic: polished black against polished white, but they were constructed of square buttons with a pleasing surface curvature. The design gave the visual impression of crosshatch latticework. Above the upper manual sat a long bank of unlabelled metal switches in two rows, all of which were in their down position, and below the bottom manual a single row of white stoppers, all pushed in.

The foot pedals where analogue to a keyboard, as expected, but were all the same, dark colour. Above them and below the lower keyboard, taking up approximately two thirds of the width of the keyboard manuals and set to the left-hand edge of the main console, I found another set of controls. These were circular and constructed of both wood and metal, the metal ones now slightly tarnished (though I expect that they had once been highly polished). These controls were clearly in three groups, but the function of those groupings wasn’t immediately apparent.

To the right of those sat another bank of controls taking up the remaining one third of the keyboard width: nine circular knobs in a three-by-three configuration and constructed of two varieties of dark, almost black, wood. They were set into a panel of even darker wood, which was the only section of the instrument’s cabinet that was of a different variety of wood.

These unusual sets of controls I describe, set vertically above the foot pedals, could by pressed, using the tips of my toes or, excepting for the lowest of them, by shifting my body position forwards on the bench and using knees, an option that at first seemed impractical and amusing, but would later prove to be essential if one was to make use of the full functionality of the instrument as I found it was possible to press a foot pedal whilst simultaneously operating a knee button (for want of a better label).

There sat a bank of hemispherical controls in a dark wood fixed into a panel located to the right of, slightly below and perpendicular to, the seating bench. This panel began flat, parallel to the floor, and then gradually curved up to meet the main body of the instrument in a position underneath some of the upper latticework controls, slightly out of view. Unlike the knee-operated controls above the foot pedals which were push-only, these controls could also be rotated by around 240 degrees (though this was difficult to gauge by eye as there were no clear makings by which I may have been able to base a more accurate approximation).

The most peculiar part of the instrument sat above the left speaker: a square metal plate set vertically into the upper cabinet panel, with a metal disc of similar thickness fixed into its centre giving it a total thickness of around 25mm. Two pieces of curved metal, each with a tapered circular cross-section, had been welded to the bottom of the plate so that they arced out and away from it. One of them arced a full 180 degrees and almost touched the wood panel; the other arced a little over 90 degrees from its base. These curved protrusions had not tarnished like the other metal components, and I wondered if they were made of a more precious metal. Ironically, to my mind, these, the most pristine elements of the instrument, were attached to it by the crudest of welds, as if metal had been haphazardly poured over the end of each of them where they met the vertical plate.

I pressed a key on the middle manual and was amazed (and perhaps a little disappointed) to hear the sound of a piano, of a hammer hitting a string. Crystal clear, and not emanating from the speakers. A comically large sliding knob to the right of the manuals and beneath the latticework controls had a spectacular effect on the sound. In the position I found it, fully to the left, all three manuals produced a sound with the timbre of a pub piano in need of turning (how would this be tuned? could a tuner even access the innards located somewhere behind these intricate dovetail joins?). Each manual behaved identically i.e. middle C sounded identical in timbre and pitch on each keyboard. Upon sliding the knob (which had a very pleasing resistance to it) fully to the right, the speakers came alive with the sound of an organ, each manual eliciting a slightly different timbre and the foot pedals producing clear sinusoidal bass tones.

What took my breath away was when I moved the sliding knob whilst continuing to play: one sound morphed seamlessly into the other. I was able to hear a more or less ‘organ-y piano’ or ‘piano-y organ’ depending on its position. Dumbfounded, I could only begin to imagine what effect the other controls, switches and panels might have.

I stood, feeling light on my feet, and embodying more than a kernel of excitement I wandered around the instrument for a second time. I had only the slightest clue as to who had made this beautiful obscurity (I assumed the previous owner, Ms xxx, who had passed several years ago, according to the agent). I had no idea if this was the work of a polymath or a team of craftspeople. The only hint at a backstory was the word PROTOTYPE written in precise pyrography on the upper left corner right-hand panel, in lettering approximately 3cm tall, but this posed more questions than it answered.

Needing to take a breath of fresh air, I stepped back over the dust covered floorboards and into the early summer sunshine to consider what I had stumbled upon and now owned (I guessed: I was not, and still am not, au fait with the intricacies of the relevant inheritance law). Looking back at PROTOTYPE through a shaft of thick, sunlit, dust-filled air, I felt as though my life, over the course of what must have been only fifteen minutes, had been fundamentally changed. I began to wonder how I might methodically explore the instrument with a view, one day, to composing music for it.

When I was given my first and only viewing a few months earlier, the agent didn’t have a key for the padlocked door to the windowless brick-built structure in the garden. She assured me that she had been inside and that the space was empty and dry. I could see for myself that the tiled roof was intact, but who knows with a building several decades old? It was a risk to commit with looking inside, but I imagined that the space would be perfect for conversion into a little music studio and workspace, hopefully without the need for any substantial structural works.

The old padlock broke easily with a pair of large bolt cutters I’d bought from a car boot sale several years earlier but had, until then, found no use for. Opening the solid oak door (situated on one of the shorter sides of the building) and expecting concrete and dank, I was astounded to find the walls, floor and rafters were clad with wood. Not a cheap laminate, but some variety of hardwood. It was dry, as I had been told it would be, and a thin layer of dust covered the floor and the large, covered object that stood slightly offset from the far-left corner. I approached, creating fresh footprints through the dust which I would later appreciate as a visual metaphor for the “one small step for man” journey I was about to embark upon.

The object was protected by a well-fitted faux leather cover. As I removed it, the not inconsiderable veneer of dust filled my face, causing me to shield my eyes with one arm and hack a cough whilst ungracefully pivoting to face the only source of fresh air in the opposite corner. Upon turning back, through settling dust and illuminated only by sunlight from that open door, I was awestruck to find myself looking at what was clearly a musical instrument, one both familiar and highly unusual. I had certainly never seen nor read a description of anything quite like what stood before me.

At first glance it was an organ with three manuals and foot pedals (and there the familiarity ended) set inside what I later found to be an exquisitely crafted wooden casing, which could only have been made by an expert cabinet maker. The seat was joined to the man body of the instrument at its base in such a way that as I entered the console area I had to step up approximately 10cm onto a platform base, on top of which was fixed the box-like seating bench.

Built into the cabinet were a pair of speakers, one either side of an unusual set of a solid-wood buttons and controls which parenthesised the keyboards in a vertical orientation. Each speaker consisted of a large driver with three small tweeters. Like the rest of the instrument, they looked to be of bespoke design. Beneath each speaker was a drawer, but I found both to be empty.

Speakers, I knew, meant electricity. This led me to the power cable that trailed from a small hole in the rear panel to a standard 240v three-pin socked, which appeared to be the only source of electricity in the building. Flicking the switch on this socket resulted in a little pop, exactly as you would expect when turning on the power to an amplifier if the volume hadn’t been turned down. After that, silence. I found myself surprised that there was no trace of electrical hum and wondered if I would be faced with disappointment when I attempted to create sound with the instrument.

I sat at the console, which was accessed from the left side of the instrument, the same side that faced the open door. The vertically set controls on either side of the keyboard had a piano-like aesthetic: polished black against polished white, but they were constructed of square buttons with a pleasing surface curvature. The design gave the visual impression of crosshatch latticework. Above the upper manual sat a long bank of unlabelled metal switches in two rows, all of which were in their down position, and below the bottom manual a single row of white stoppers, all pushed in.

The foot pedals where analogue to a keyboard, as expected, but were all the same, dark colour. Above them and below the lower keyboard, taking up approximately two thirds of the width of the keyboard manuals and set to the left-hand edge of the main console, I found another set of controls. These were circular and constructed of both wood and metal, the metal ones now slightly tarnished (though I expect that they had once been highly polished). These controls were clearly in three groups, but the function of those groupings wasn’t immediately apparent.

To the right of those sat another bank of controls taking up the remaining one third of the keyboard width: nine circular knobs in a three-by-three configuration and constructed of two varieties of dark, almost black, wood. They were set into a panel of even darker wood, which was the only section of the instrument’s cabinet that was of a different variety of wood.

These unusual sets of controls I describe, set vertically above the foot pedals, could by pressed, using the tips of my toes or, excepting for the lowest of them, by shifting my body position forwards on the bench and using knees, an option that at first seemed impractical and amusing, but would later prove to be essential if one was to make use of the full functionality of the instrument as I found it was possible to press a foot pedal whilst simultaneously operating a knee button (for want of a better label).

There sat a bank of hemispherical controls in a dark wood fixed into a panel located to the right of, slightly below and perpendicular to, the seating bench. This panel began flat, parallel to the floor, and then gradually curved up to meet the main body of the instrument in a position underneath some of the upper latticework controls, slightly out of view. Unlike the knee-operated controls above the foot pedals which were push-only, these controls could also be rotated by around 240 degrees (though this was difficult to gauge by eye as there were no clear makings by which I may have been able to base a more accurate approximation).

The most peculiar part of the instrument sat above the left speaker: a square metal plate set vertically into the upper cabinet panel, with a metal disc of similar thickness fixed into its centre giving it a total thickness of around 25mm. Two pieces of curved metal, each with a tapered circular cross-section, had been welded to the bottom of the plate so that they arced out and away from it. One of them arced a full 180 degrees and almost touched the wood panel; the other arced a little over 90 degrees from its base. These curved protrusions had not tarnished like the other metal components, and I wondered if they were made of a more precious metal. Ironically, to my mind, these, the most pristine elements of the instrument, were attached to it by the crudest of welds, as if metal had been haphazardly poured over the end of each of them where they met the vertical plate.

I pressed a key on the middle manual and was amazed (and perhaps a little disappointed) to hear the sound of a piano, of a hammer hitting a string. Crystal clear, and not emanating from the speakers. A comically large sliding knob to the right of the manuals and beneath the latticework controls had a spectacular effect on the sound. In the position I found it, fully to the left, all three manuals produced a sound with the timbre of a pub piano in need of turning (how would this be tuned? could a tuner even access the innards located somewhere behind these intricate dovetail joins?). Each manual behaved identically i.e. middle C sounded identical in timbre and pitch on each keyboard. Upon sliding the knob (which had a very pleasing resistance to it) fully to the right, the speakers came alive with the sound of an organ, each manual eliciting a slightly different timbre and the foot pedals producing clear sinusoidal bass tones.

What took my breath away was when I moved the sliding knob whilst continuing to play: one sound morphed seamlessly into the other. I was able to hear a more or less ‘organ-y piano’ or ‘piano-y organ’ depending on its position. Dumbfounded, I could only begin to imagine what effect the other controls, switches and panels might have.

I stood, feeling light on my feet, and embodying more than a kernel of excitement I wandered around the instrument for a second time. I had only the slightest clue as to who had made this beautiful obscurity (I assumed the previous owner, Ms xxx, who had passed several years ago, according to the agent). I had no idea if this was the work of a polymath or a team of craftspeople. The only hint at a backstory was the word PROTOTYPE written in precise pyrography on the upper left corner right-hand panel, in lettering approximately 3cm tall, but this posed more questions than it answered.

Needing to take a breath of fresh air, I stepped back over the dust covered floorboards and into the early summer sunshine to consider what I had stumbled upon and now owned (I guessed: I was not, and still am not, au fait with the intricacies of the relevant inheritance law). Looking back at PROTOTYPE through a shaft of thick, sunlit, dust-filled air, I felt as though my life, over the course of what must have been only fifteen minutes, had been fundamentally changed. I began to wonder how I might methodically explore the instrument with a view, one day, to composing music for it.