LITTLE ENGLAND

|

Little England - a chamber opera in nine scenes

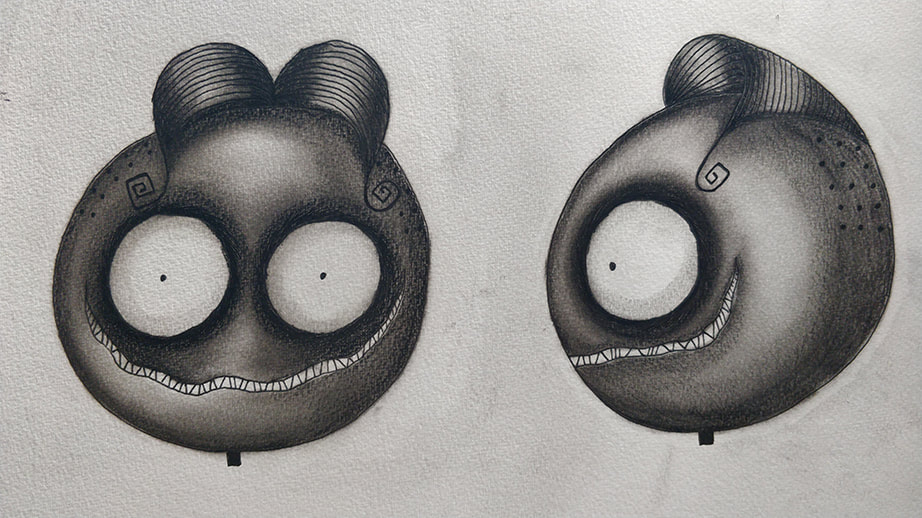

Music by Mark Bowler Libretto by Gareth Mattey Jack – Nathan Mercieca Jill – Shakira Tsindos The Miniaturist – Andrew Randall Artwork and character design by Sam Haynes LISTEN AND SUPPORT ON BANDCAMP LISTEN ON SPOTIFY |

SYNOPSIS

In a lonely little corner of little England, Jack and Jill appear to us with a problem. The famous duo informs us that there is a monster nearby, a Miniaturist, who lives in isolation, preying upon children and those alone after dark. They reassure us he is a threat that needs dealing with and that they are up to the challenge, and to trust them as they set off on their adventure to slay the monster. But the Miniaturist isn't what they said - a quiet man, a conscientious man, living alone and building a model world in miniature in his home. When Jack and Jill arrive, professing to need help, he lets them in, only for the fairy tale pair to attack him and knock him out with their trusty hammers. They subject him to threats, to insults, to violence and to seemingly impossible riddles as they expose who he really is - a gay man, shunned and alone, having fled a society that rejects him and those he would love. As Jack and Jill delight in exposing all of his secrets, the quiet man explodes with anger, turning their riddles against them and mercilessly beating them to death with their own hammers. The Miniaturist, realising that the bigots and monsters will seek him out even here, resolves to leave behind his isolation and refuses to hide away anymore. Amidst the shattered remains of his little England, Jack and Jill rise again in laughter to claim this had been their goal all along - that their violent actions were charitable, necessary, and wholly English. As they cheerily wave us goodbye, they assure us it will not be long before their 'services' are required again... |

BACKGROUND

Gareth and I began discussing ideas for an opera in summer of 2019 following a couple of successful, small-scale collaborative projects. This would be my first foray into the artform. Like our previous work, we knew this piece would explore queer themes and although we had the enthusiasm, we lacked a clear subject to investigate.

Gareth, never one to be short of pithy ideas for pieces or titles, had wanted to make a piece called The Miniaturist, a tale about a character building a miniature world as a form of escapism. The idea lacked the answer to 'why?'

I, never one to be short of over-complicated ideas, had been exploring Tinker's House, an abandoned cottage in rural Suffolk. At the time of writing it is still accessible, though only by foot and after a twenty minute walk from the closest neighbours. If you are willing to take the risk of exploring a small, burnt-out, partially collapsed cottage you will find a time capsule: decades old furniture, kitchenware, and food packaging, and an eclectic selection of books with topics ranging from poetry to the technicalities of sailing, via the physical sciences, mathematics and psychology, all coexisting in a space in which the boundary between inside and outside has become blurred by an invasion of ivy.

Gareth and I began discussing ideas for an opera in summer of 2019 following a couple of successful, small-scale collaborative projects. This would be my first foray into the artform. Like our previous work, we knew this piece would explore queer themes and although we had the enthusiasm, we lacked a clear subject to investigate.

Gareth, never one to be short of pithy ideas for pieces or titles, had wanted to make a piece called The Miniaturist, a tale about a character building a miniature world as a form of escapism. The idea lacked the answer to 'why?'

I, never one to be short of over-complicated ideas, had been exploring Tinker's House, an abandoned cottage in rural Suffolk. At the time of writing it is still accessible, though only by foot and after a twenty minute walk from the closest neighbours. If you are willing to take the risk of exploring a small, burnt-out, partially collapsed cottage you will find a time capsule: decades old furniture, kitchenware, and food packaging, and an eclectic selection of books with topics ranging from poetry to the technicalities of sailing, via the physical sciences, mathematics and psychology, all coexisting in a space in which the boundary between inside and outside has become blurred by an invasion of ivy.

At one time you would have seen the remains of a grand piano protruding from the rubble caused by the collapse of the roof and upper floor, but it is only evidenced now via rare photographs, including the one below taken in 2010 by Tom Heller.

Who had once lived here? Who had abandoned a piano and a library?

I spoke with several locals who had known the man who had once lived at Tinker's House. His name was Robert James and he was an enigmatic and isolated member of the community, living a hermit's life out on the marsh. He was clearly an unwell man and after twice settling fires within his home, the second of which caused the roof to collapse, he was offered the care he needed.

Exactly why this intellectual musician had isolated himself, and the reasons behind his mental decline, remained a mystery. Several possibilities were offered to me, all of which were corroborated to an extent and seemed plausible. Only one smacked of outright rumour: that he was a gay man in denial, hiding from himself and the world. This seemed far too intimate a detail for anyone to know about a man who was prone to throw stones at people who came too close to his home. But it did provide the missing piece to our puzzle.

An isolated cottage. A hermit-like miniaturist. A rumour. Add a couple of villainous, self-righteous, pernicious children in the form of folk-horror versions of Jack and Jill (of nursery rhyme fame) and you have the basis for Little England.

I spoke with several locals who had known the man who had once lived at Tinker's House. His name was Robert James and he was an enigmatic and isolated member of the community, living a hermit's life out on the marsh. He was clearly an unwell man and after twice settling fires within his home, the second of which caused the roof to collapse, he was offered the care he needed.

Exactly why this intellectual musician had isolated himself, and the reasons behind his mental decline, remained a mystery. Several possibilities were offered to me, all of which were corroborated to an extent and seemed plausible. Only one smacked of outright rumour: that he was a gay man in denial, hiding from himself and the world. This seemed far too intimate a detail for anyone to know about a man who was prone to throw stones at people who came too close to his home. But it did provide the missing piece to our puzzle.

An isolated cottage. A hermit-like miniaturist. A rumour. Add a couple of villainous, self-righteous, pernicious children in the form of folk-horror versions of Jack and Jill (of nursery rhyme fame) and you have the basis for Little England.

The libretto has a timeless quality. By that, I mean that it is impossible to place the story historically. It is, however, firmly located in its Englishness. I responded to this by using a contemporary musical vocabulary coupled with quotation (and parody) from various English composers and children’s songs. This is most explicit in scene six, in which The Miniaturist sings an aria I (re)named Land of Shame and Despair - an ironic subversion of Elgar's Land of Hope & Glory.

With their libretto for Little England, Gareth has created a twisted folk-horror anti-morality play which results, when viewed through the darkly comedic lens Gareth provides, in a truly anarchic and disturbing fairy tale. Without the fourth wall (which is torn down immediately in the opening scene) the audience become complicit in the violence and tied up in moral knots they can't comfortably laugh their way out of. I couldn't have asked for more inspiration from a libretto.

As work on the opera was underway, and with our sights set on a confirmed staging at Milton Court Studio Theatre in London in June of 2020, the pandemic arose. This project was one of the many that were necessarily cancelled without being rescheduled.

With their libretto for Little England, Gareth has created a twisted folk-horror anti-morality play which results, when viewed through the darkly comedic lens Gareth provides, in a truly anarchic and disturbing fairy tale. Without the fourth wall (which is torn down immediately in the opening scene) the audience become complicit in the violence and tied up in moral knots they can't comfortably laugh their way out of. I couldn't have asked for more inspiration from a libretto.

As work on the opera was underway, and with our sights set on a confirmed staging at Milton Court Studio Theatre in London in June of 2020, the pandemic arose. This project was one of the many that were necessarily cancelled without being rescheduled.

“…folk horror is an apposite genre for our times, as it demythologises the idea of Britain’s ‘gloriousness’… and exposes the strange and some-times violent history of our countryside. Far from Britain being a green and pleasant land built on ancient codes of honour, it’s the place where we hanged people, where battles were fought, where murders were committed, where the rich beat the poor into submission.” “[In his late 1990’s TV series Jam, Chris Morris was] interested in tying people in moral knots – giving them a moral problem and then…twisting it so they have to do something awful to get out of the first moral problem….making them laugh in a way that they’re not used to.” |

PLAN B

We had put too much work into the project for it to exist only on paper, but a staging was impossible. Instead, I decided that I would self-finance and produce an oddity: a recording of an opera that had never been staged. I prepared click tracks and midi versions of the music and sent personalised recording templates to each player and singer. In turn, during the first lockdown, they recorded themselves performing four of the nine scenes. That would be enough material, I thought, to give a flavour of the opera to tout around once the pandemic was over.

I then began the complicated task of piecing together a complete recording from the parts and finding ways of getting audio files of varying quality to sit with each other as if the ensemble had been recorded together in a studio.

What had been a sad project, doomed to be unseen by the world, was now perhaps sadder still: a half told story. And so, when funds allowed, I commissioned the recording of the remaining five scenes, which helped fill the days during a later lockdown.

By summer of 2021, two years after work had begun, Gareth and I had a complete recording. This musical amalgamation was sounding pretty polished, probably better than I had expected it to, and as restrictions on socialising were lifted we rerecorded a handful of the parts again in slightly more controlled environments (I had been struggling to remove passing buses / aeroplanes / housemates from a few of the recordings!). This necessitated completely remixing the project and in the midst of this I became a father. Suddenly, it was summer 2022 and three years had passed. But we had a recording to be proud of.

We had put too much work into the project for it to exist only on paper, but a staging was impossible. Instead, I decided that I would self-finance and produce an oddity: a recording of an opera that had never been staged. I prepared click tracks and midi versions of the music and sent personalised recording templates to each player and singer. In turn, during the first lockdown, they recorded themselves performing four of the nine scenes. That would be enough material, I thought, to give a flavour of the opera to tout around once the pandemic was over.

I then began the complicated task of piecing together a complete recording from the parts and finding ways of getting audio files of varying quality to sit with each other as if the ensemble had been recorded together in a studio.

What had been a sad project, doomed to be unseen by the world, was now perhaps sadder still: a half told story. And so, when funds allowed, I commissioned the recording of the remaining five scenes, which helped fill the days during a later lockdown.

By summer of 2021, two years after work had begun, Gareth and I had a complete recording. This musical amalgamation was sounding pretty polished, probably better than I had expected it to, and as restrictions on socialising were lifted we rerecorded a handful of the parts again in slightly more controlled environments (I had been struggling to remove passing buses / aeroplanes / housemates from a few of the recordings!). This necessitated completely remixing the project and in the midst of this I became a father. Suddenly, it was summer 2022 and three years had passed. But we had a recording to be proud of.

The cherry on top came in the form of Sam Haynes, who offered his artistic skills to help visualise the characters. The result is the creepy, blood-splattered artwork that accompanies the recording.

Finally, a subtitled video. My work here is done.

But perhaps it isn't.... we would love for this piece to be staged or for an animation to be made to accompany it. Is this something you or someone you know could help us achieve? Please get in touch if you can help us bring Little England to a wider audience.

- Mark Bowler, November 2022

Finally, a subtitled video. My work here is done.

But perhaps it isn't.... we would love for this piece to be staged or for an animation to be made to accompany it. Is this something you or someone you know could help us achieve? Please get in touch if you can help us bring Little England to a wider audience.

- Mark Bowler, November 2022

|

Little England

Music – Mark Bowler Libretto – Gareth Mattey Jack – Nathan Mercieca Jill – Shakira Tsindos The Miniaturist – Andrew Randall Flute / Piccolo – Enlli Parri Clarinet / Bass Clarinet – Raymond Brien Trumpet – Tom Kearsey Piano – Natalie Burch Percussion – Aidan Marsden Violin – Lara Agar Cello – Polly Bowler Character design and artwork – Sam Haynes Amalgamated, mixed and mastered by Mark Bowler at One Glass Eye Studios, 2020-2022. Special thanks to Matthew King, Julian Philips, and James Alexander at Guildhall School of Music & Drama. Recording © Copyright 2022 One Glass Eye Records Music © Copyright 2020 Mark Bowler Libretto © Copyright 2020 Gareth Mattey |

Track list:

01 - Scene 1: First Words - in which Jack and Jill prepare us for the story to come

02 - Scene 2: Little Worlds - in which we see the Miniaturist at work

03 - Scene 3: First Laughs - in which the Miniaturist’s peace is disturbed

04 - Intermission No. 1

05 - Scene 4: A Little Riddle -in which the Miniaturist is posed his first question

06 - Intermission No. 2

07 - The Middle Riddle - in which the Miniaturist is posed his second question

08 - Intermission No. 3

09 - Scene 6: The Final Riddle - in which the Miniaturist is posed his final question and offers an answer

10 - Scene 7: Last Laughs - in which the Miniaturist has the last laugh without laughing

11 - Scene 8: Little Left - in which we see the Miniaturist abandon his work

12 - Scene 9: Last Words - in which Jack and Jill offer a defence of their actions

01 - Scene 1: First Words - in which Jack and Jill prepare us for the story to come

02 - Scene 2: Little Worlds - in which we see the Miniaturist at work

03 - Scene 3: First Laughs - in which the Miniaturist’s peace is disturbed

04 - Intermission No. 1

05 - Scene 4: A Little Riddle -in which the Miniaturist is posed his first question

06 - Intermission No. 2

07 - The Middle Riddle - in which the Miniaturist is posed his second question

08 - Intermission No. 3

09 - Scene 6: The Final Riddle - in which the Miniaturist is posed his final question and offers an answer

10 - Scene 7: Last Laughs - in which the Miniaturist has the last laugh without laughing

11 - Scene 8: Little Left - in which we see the Miniaturist abandon his work

12 - Scene 9: Last Words - in which Jack and Jill offer a defence of their actions